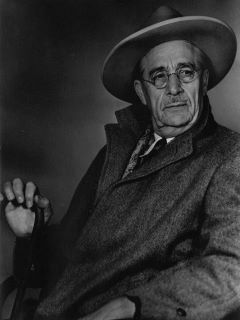

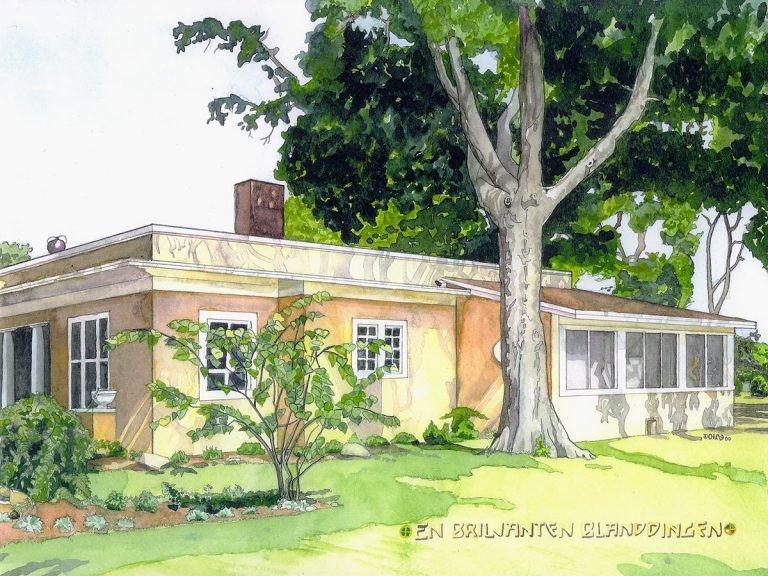

Image: The Jacobson House by America Meredith, Courtesy Jacobson House Native Art Center.

This past summer HAHS had the pleasure of working with and mentoring two interns through the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s summer intern program. Both interns were given the freedom to explore research focused projects of their own choosing, with an intention to bring forward artistic legacies and sites that widen the lens through which art history can be examined. Their projects represent our ongoing commitment to use our work, membership, and platform to tell a broader and deeper story through HAHS. This blog features the work of one of these interns, Blue Tarpalechee.

Oscar Jacobson, the Kiowa Six, and linked legacies

By Blue Tarpalechee

Just one block from the University of Oklahoma campus in Norman, Oklahoma, on the corner of Chautauqua and Boyd sits an adorable little house that looks like it’s been plucked from the Mediterranean. Its columns and doors rest in the shade of giant oak and cottonwood trees that line the neighborhood’s streets, their size and grandeur suggesting a sense of permanency and security—like the folks who planted those trees knew that they’d be creating a legacy. For this house, in particular, that legacy crosses oceans and represents nations. It remembers what was and celebrates what is to come. It is the Oscar B. Jacobson House, the subject of my nascent research and the nexus of some of the most incredible stories of Oklahoma’s art history.

My project for the Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios program was inspired by the terms used in the name of the program itself and my personal stubborn habit of positioning Native people and communities in spaces that don’t always have them in mind. When thinking about each of the terms in the HAHS acronym, I wanted to unsettle the typical settler notions associated with them where possible, feasible, and appropriate. Whose history and what makes one historical? What arts make one an artist? What does home mean? What about artists whose studios aren’t around anymore, or whose studios were a shared space? After initial discussions with my supervisor, I was pleased to learn that this kind of exploration was encouraged. With her support, I think the project was successful in mapping a bit of complexity and nuance in the conversation while also enriching the research for my dissertation project as a PhD candidate. My interests in authorial custody and story stewardship intersect nicely with an examination of the Kiowa Six and Oscar Jacobson, particularly around questions of stewardship, authorship, and legacy. To get to the heart of these questions while satisfying the spirit of the HAHS program’s goals, I began to investigate the nature of Jacobson’s patronage of the Kiowa Six, and how the house embodies that story.

Oscar Jacobson: Builder

Oscar Brousse Jacobson (1882–1966) was a young boy when his family immigrated to America from Sweden in 1890. The family settled near Lindsborg, Kansas, which at the time was a budding college town on the prairie known as “Little Sweden” for its large Swedish immigrant population. Jacobson would go on to attend Bethany College there in Lindsborg where he would study art under another Swede, Birger Sandzen (1871–1954), whose influence on Jacobson’s style is immediately evident. Upon graduation, Jacobson began working with the Royal Swedish Commission of the 1904 World’s Fair held in St. Louis, Missouri, where he served as art attache and assistant to Anshelm Schultzberg (1862–1945).

In 1912 he married a French-born art historian, Sophie Brousse (also known by her pen name Jeanne d’Ucel) and took her surname, adding it to his own in a very progressive move for the time. Later, Jacobson would acquire his Bachelors of Fine Arts degree from Yale University and teach at two small colleges before joining the University of Oklahoma in 1915. He would remain attached to the University for the remainder of his life and took the fledging art program from a single room with a handful of students to an internationally respected department with three campus buildings, dozens of instructors, and hundreds of students.

Image: The Jacobson House, Courtesy of Blue Tarpalechee.

Shortly after arriving in Norman, Jacobson and his wife committed themselves to build a house that their growing family could call home. Despite the material shortages of World War I and the logistical difficulties of living with the sparse infrastructure of the then three-years-old state of Oklahoma, Jacobson was able to construct his Pompeian home. Designed by Jacobson himself, the house was an eclectic mix of Italian Renaissance cornices, Mediterranean columns and arches, and Santa Fe-style adobe-like walls. Like many artists before and since, Jacobson ensured light and space were a priority throughout the house. Every room has an outside view, culminating in an atrium-like veranda where the family and guests often took meals. The space was inviting and the family would welcome artists and musicians frequently.

Today, the Jacobson House remains a gathering space for members of the Norman, University, and Native American communities it has historically served. Throughout the year visitors will find art exhibitions, Native drum circles, youth competitions, plein air painting, and open gallery sessions that keep the House bustling with activity. Its grounds and facilities are beautifully maintained by the University, including a recent restoration of the basement, which has its own important place in history as the studio of the Kiowa Six.

The Kiowa Six

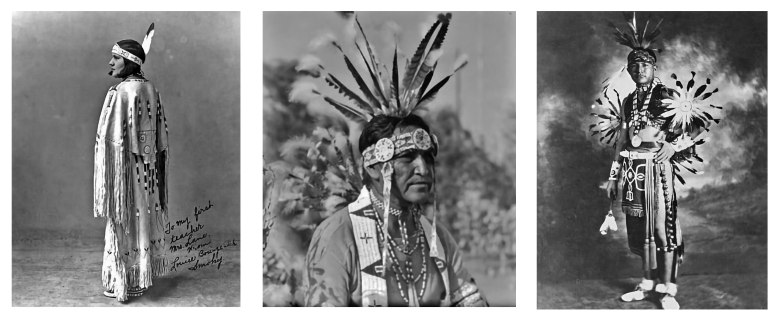

Most of this early history and more, fascinating as it is, was unknown to me—and indeed, to many— in large part because Jacobson’s most significant contribution to the art world was his role as patron to the Kiowa Six. In 1927, Jacobson began to host a select few Kiowa artists in his home as they pursued their arts education at the University. The Kiowa Six—Stephen Mopope (1898–1974), Lois Smoky Kaulaity (1907–1981), Jack Hokeah (1901–1969), Monroe Tsatoke (1904–1937), Spencer Asah (1908–1954), and James Auchiah (1906–1974)—gained international recognition through Jacobson’s promotional efforts and were instrumental in Native art traditions being recognized by the world at large as fine art for the first time. Jacobson, along with his colleague Edith Mahler, adhered to a hands-off approach in order to minimize their influence on the development of the Kiowa Six’s art practice. Theirs was an art practice that started in the community, moved through the basement and into the classroom, then ultimately ended up on the world stage and would serve as a catalyst for countless other Native artists passing through the University of Oklahoma’s Art Department under Jacobson’s leadership. Jacobson repeatedly and enthusiastically encouraged Native artists to look to their cultures and elders for inspiration and a unique path to the enrichment of the American art story.

Images: The Kiowa Six - from left to right: Lois Smoky Kaulaity (1907–1981), Jack Hokeah (1901–1969), and James Auchiah (1906 – 1974), Courtesy Jacobson House Native Art Center.

What interests me most about this research is how entwined life and land reveal themselves to be. The story of the Kiowa Six is inexorably linked to the story of Oscar Jacobson, who by way of his position at the University is linked to the story of the land itself—and it isn’t without tension. Jacobson’s legacy, in large part, is accounted for by the legacy of his students and their time in his home. Contemporary sensibilities require a critical look at Jacobson’s patronage and the complex systems informing the status quo of the time in question. It encourages readers to inquire into the nature of a number of topics, including race, the art market, identity, legacy, and place. Simply put, one cannot explore the historical significance of the Kiowa Six without contending with the historical significance of Oscar Jacobson—and that dependency has often been a polarizing subject. To further illustrate the nuances at work complicating these issues, the land itself had only come under white ownership a generation prior and the Kiowa traditionally roamed the region. All of these factors contribute to a productive examination of what “home” can mean, and how that meaning is informed and changes over time. While this project can’t hope to answer all of the questions it poses, I still found the process edifying and hope to engage with these complex matters more thoroughly in my future work.

Images: The Kiowa Six - from left to right: Spencer Asah (1906–1954), Stephen Mopope (1898–1974), and Monroe Tsatoke (1904–1937), Courtesy Jacobson House Native Art Center.

Looking at Legacy

Image: Oscar B. Jacobson and five of the Kiowa Six artists, Courtesy Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. 1996.017.1039.13279

I settled on this topic of study not because of Jacobson, but frankly in spite of him. One cannot study the Kiowa Six without studying Jacobson to a certain extent, though to be fair his involvement would not be so exaggerated were it not for his home having served as their studio. And as I discovered, a rigorous examination of the house itself necessitates an exploration of Jacobson, the Six, the school, the state, the land, and the nations involved. I mention this because it is worth considering how base assumptions or preconceptions of what “home” and “studio” mean for the Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios program can dictate the direction researchers might initially orient themselves. Thanks to the support of the Director, Valerie Balint, these inquiries, and more, are encouraged rather than avoided.

Images: Left: Emerald Lake No. 1 by Oscar Jacobson (1882–1966). Oil on canvas board, 20 x 26 in. The Oklahoma Arts Council, purchased through a National Endowment for the Arts grant, 1971. Right: Mountain View by Jacobson, undated. Oil on panel, 12 1/2 x 18 1/2 in.

With the freedom to pursue these difficult topics, an initial guiding question came to the forefront of my research: is Jacobson significant because of the Kiowa Six, or are the Kiowa Six significant because of Jacobson? Eventually, the question took on a more sophisticated form but it remained an underlying impetus for new inquiries. We can continue to debate this question and its constituent parts as well, because of course, the question has its own internal problems. It presents a binary where in reality so few things actually are; it questions significance, treating it as a catch-all term that combines importance, fame, consequence, and more—each of which will hold different weight depending on who is attempting to answer the question. In short, it at once oversimplifies the issue while also distilling it down to what ultimately matters to me, if no else.

Images: Left: In the Grand Atlas by Jacobson, undated. Oil on canvas. Right: The Red Tank or Indian Pool by Jacobson, 1940. Oil on canvas, 22 x 28 in. Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, The University of Oklahoma, Norman; Gift of Robert Long.

I think knowledge seekers should lean into those opportunities when they arise, and that was certainly the case here. My search took me to new locations, sparked conversations with experts, and deepened my appreciation for a number of previously unknown artists and educators. Jacobson’s contemporaries were, like Jacobson himself, hugely influential as art educators and administrators. Folks like Doel Reed (1894–1985), Edith Mahier (1892–1967), Mary Stone McLendon (1896–1967), also known as Princess Ataloa, Willie Baze Lane (1896–1947), and Sister Mary Olivia Taylor (dates unknown) all had a hand in shaping the landscape of art education in Oklahoma. Jacobson’s influence extends to artists working today through some of his more direct connections to folks like Olinka Hrdy (1902–1987), Ina Annette (1901–1990), Dick West (1912–1996), Acee Blue Eagle (1907–1959), and Yeffe Kimball (1906–1978), each of whom were breaking ground with their own styles. It was in the spirit of acting upon Jacobson’s influence and inspiration that I settled on a final creative aspect of this research. Like the hundreds of students Jacobson taught in his lifetime and the countless he’s inspired since, I wanted to honor the man and the story that encouraged a closer look.

Twin Legacies

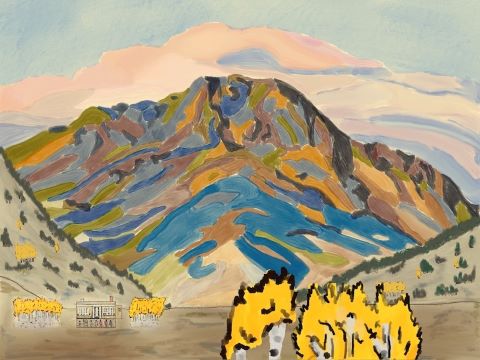

Image: Twin Legacies by Blue Tarpalechee, 2023. Creative Commons.

This project challenged me to convey the host of themes and histories that a study of Jacobson unearths. As I set out to produce what was originally intended to be an artistic family tree for Jacobson that looked at his predecessors, peers, and students, it became clear that one tree simply wouldn’t do for a man like Jacobson, whose influence as an educator spanned decades and hundreds of students. Then I thought back to the house, and to the roots of that house, and how Jacobson had a role in the flourishing of a completely separate family of artists. I took that initial thread and tried to capture the broad scope of these ideas. Inspired by Jacobson’s oil painting “Twin Peaks,” I call this painting “Twin Legacies.” The first and most immediate element that catches the viewer's eye is the distant mountaintop and cloud cover. These are painted in the style of Jacobson while also representing the monumental impact of his work. That impact is the intertwined combination of his legacy and that of the Kiowa Six, whose work he was instrumental in bringing to the highest reaches of the world’s fine art stage. In the foreground is the Jacobson house, with the Kiowa Six occupying the basement just as they did in 1927.

Here, as in actual history, Lois Smoky is separate from but still included with the other Kiowa Five, a result of lingering gender discrimination in both their field and their time. On either side of the Jacobson house and populating the distant foothills are groves of Aspen trees. These trees are found in Jacobson’s home of Sweden as well as dotting the landscapes of the mountain ranges of the American West, where Jacobson would call home and paint prolifically. One of the unique aspects of these groves is that the Aspen has a lateral root system connecting all the trees we see above ground. As the viewer’s eye moves across the painting, the leftmost grove represents the European art tradition that Sandzen and Jacobson and countless others were a part of. The House itself serves as the liminal space between that tradition and the tradition of Native American communities’ art practices. To be clear, they’ve always existed, but Jacobson was very influential in giving the world an opportunity to recognize these traditions as fine art and as distinct from the conventions they were accustomed to. A study of Jacobson is a study of Native art, Western art, American art, and European art. His home was a meeting place of diverse cultures and styles, and it is only fitting that its history continues to be celebrated in that way.

About the Author - Blue Tarpalechee

Blue Tarpalechee is an enrolled citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. He is a Ph.D. candidate in the English department of the University of Oklahoma, where his research centers around Native American literature. Using Muscogee artists and authors as his foundation, Blue’s work examines the semiotics of the Native image and probes the boundaries of authorial custody and story stewardship. He received his MFA in Creative Writing from the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico in 2019. He is the proud father of two boys and flabbergasted by his luck to be the partner of a brilliant Anishinaabe woman. Originally from Okmulgee, Oklahoma, Blue now spends his days writing a dissertation in Norman, Oklahoma, and his evenings with family at ball games across the state.