Farm to easel: Florence Griswold show focuses on artwork of New England farms

Published by The Day, May 27. 2018 12:01AM | Updated May 27. 2018 4:36PM

By Kristina Dorsey, Day staff writer

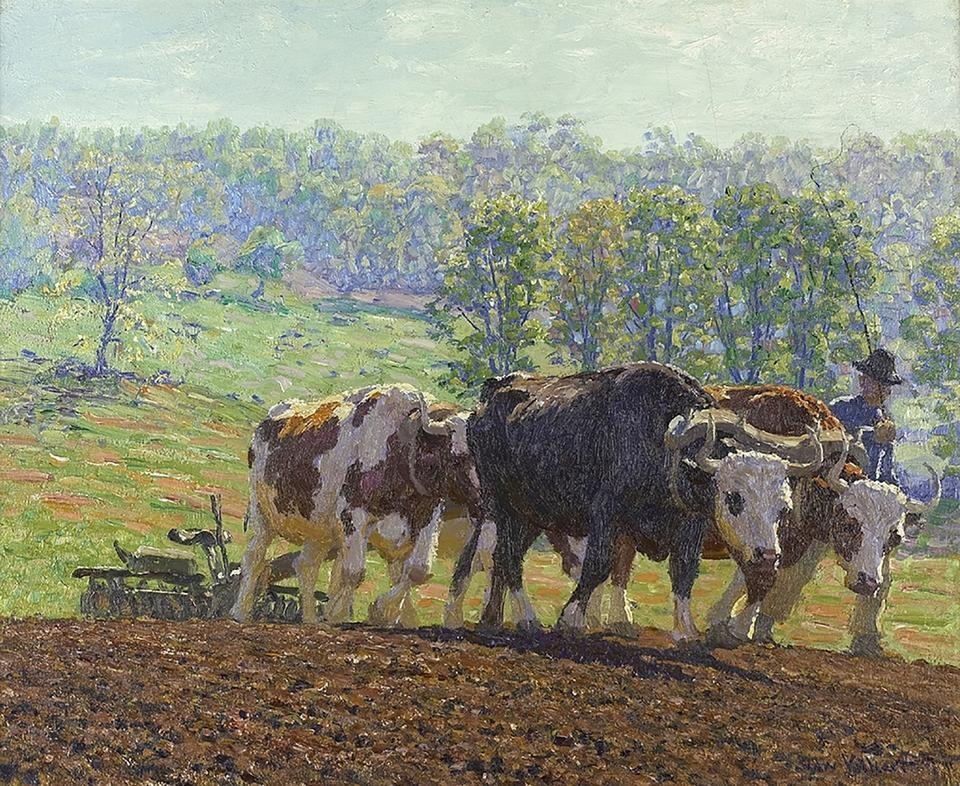

Image: “Harrowing,” oil on canvas, by Edward C. Volkert (1871–1935)

Bucolic paintings of farms are a bit of quintessential New England imagery — lush fields, rustic stone walls, grazing animals, hardworking farmers.

A new exhibition at the Florence Griswold Museum goes beyond that iconic picture to examine the progression of those farms’ histories and the art that captured the evolution.

“Art and the New England Farm” travels from the height of farming’s popularity here in the 1800s through its decline. It touches, too, on a couple of specific local farms: one that existed at the Florence Griswold property in Old Lyme and Tiffany Farms in Lyme, which was a dairy farm up until last year and is now home to a small herd of cows used to breed.

Through it all, the exhibition examines how artists captured the ever-changing New England farm.

“Now, when someone says an American farm, something by Grant Wood (whose art focused on the Midwest) pops into people’s minds,” says Florence Griswold Museum Curator Amy Kurtz Lansing. “But really the image that all of us have socked away about what a farm is like, no matter where it is, … the kernel of (that image) comes from the New England farm.”

Kurtz Lansing was originally thinking of calling the exhibition “The New England Farm,” but adding “Art” to the title was an important change.

“Artists have had this huge role in defining farms in our imagination over time, especially people like (Connecticut painter George Henry) Durrie, who is highlighted in the show,” she says. “They are the people who are kind of stitching together these views of what farms look like. Then, because their images are reproduced and spread so widely in print, they become pervasive in our national imagination, corresponding to ideas that the artists themselves didn’t necessarily create about the yeoman farmer, a concept that comes from Thomas Jefferson about the farmer, the individual landowner, as being this sort of quintessential citizen.”

The artists created images like that and then repeated them in their work, some into the 20th century. Even if these paintings of idyllic independent farms didn’t correspond with reality, viewers who had moved to cities wanted to see pictures that reminded them of their own rural past.

Durrie is known as a painter of winter scenes (an example is “Seven Miles to Farmington,” which is part of “Art and the New England Farm”), and he often focused on farms and farm yards as little complexes unto themselves — the essence of country life all in one place. His pictures were reproduced by Currier & Ives, which spread Durrie’s vision to people all over the country. As the exhibition notes, Durrie helped popularize landscapes celebrating the independent family farm.

“Art and the New England Farm” highlights a range of artists’ approaches to farms, from the sumptuously pastoral scene of Carleton Wiggins’ “Seaside Sheep Pastures” to Walker Evans’ stark black-and-white photo “Early Dawn Farm, Rt. 156, Lyme.”

Some pieces provide a window into particular aspects of farming. Edward Volkert’s painting “Harrowing,” for instance, depicts harrowing of the fields, showing what appear to be oxen pulling the machinery that helped to level and root up weeds in plowed land.

George Glenn Newell, meanwhile, was inspired to create “Salt Haying, Old Lyme” in 1906 when he saw farmers gathering salt hay from marshes along the Connecticut River. (This painting was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1907 and is new to the Florence Griswold Museum’s collection.) Kurtz Lansing points out that this painting encapsulates how farmers adapted to conditions here. They were using a resource — salt hay — that’s abundant in this region, and it’s something that could be used here and could be sold farther afield as feed and fertilizer. In this area, there weren’t many crops like that at the turn of the 20th century.

“At the mouth of the Connecticut River, there were ample salt marshes that farmers in the region had been exploiting for centuries, continuing to do so even when other agricultural outputs had declined,” she says.

The toll that humans took

“Art and the New England Farm” offers an array of interesting tidbits, including this: in 1922, “Scientific American” reported that “‘throughout Old Lyme and Hamburg, Conn., you are welcome to wander over farm property — unless you are an artist. Signs everywhere forbid artists to trespass; the reason given is that many cows have been poisoned by paint-incrusted rags thrown away by the colorists.’”

“It really speaks to this relationship of what is the position of farms once other people are using the countryside for nonagricultural reasons — like these artists coming in as weekend and summer visitors and then poisoning the cows with their turpentine rags,” Kurtz Lansing says.

Over time, the number of farms in America at large began to dwindle. The factors that contributed to that change include industrialization, but Kurtz Lansing says it was more than that: “Really, this quest to go out and always find what is the best, ideal land and make a new farm in that place, that’s really driving the settlement of the United States from the beginning. There are people, from the Puritans on, who are saying, ‘Well, I’m going to look over here and make my farm there and go west and look for something there.’ Then industrialization exacerbates that.”

Other factors were at work, too. One is exemplified by the image in Martin Lewis’ 1933 painting “Dawn, Sandy Hook, Connecticut,” with its dark, moody view of nearly identical, boxy houses set against a just-brightening sky.

“The picture itself is about how artists and people from the city move out to the country because they appreciate being closer to the farm and back to nature, back to the earth, back to the land. But then their very presence there reduces the amount of open space, because they’re building houses, these cookie-cutter suburban houses (as depicted in the painting),” Kurtz Lansing says. “I feel that is really so relevant because it speaks to the loss of farm land and pressures on farm land.”

So while New England farms were being abandoned, they were also disappearing because they were becoming suburban yards.

The Griswold and Tiffany farms

Florence Griswold’s property had its own small family farm for a time, starting in 1899. The Griswolds grew produce from potatoes to strawberries, with the help of laborers, many of whom were immigrants. The family didn’t make their living by farming (Florence’s father was a ship captain), and their farming was more for personal use.

“We tend to focus on this property as a home to artists and as the place they came to stay at the boarding house and to paint,” Kurtz Lansing says. “But I think it was really an important reminder that the property itself had this life as a farm. And that’s part of what drew artists to it — that it had these fruit trees growing and (the artists) being able to identify its picturesque qualities that were actually agrarian.”

The final segment of “Art and the New England Farm” focuses on Tiffany Farms in Lyme. Judy Friday spent 2003 in residence at the site, and her photographs — featured in the exhibition and published in her own 2003 book — captures images of cows and fields and the humans who worked there. The farm, which the Tiffany family began running in 1841, had long drawn artists to it. Rising costs and declining profits for milk, though, prompted the family to cease operating the site as a dairy farm last year.

Kurtz Lansing notes that, even though there is an increased interest in farm-to-table cuisine and in buying high-quality local produce, many farms cannot make things work financially these days.

“Art and the New England Farm” is a wide-ranging exploration of its subject, and Kurtz Lansing says she hopes visitors will “take their interest in farms and foods and really understand what has made farming in New England what it is, admire the kind of adaptability to the environment and the geology and help support its vitality.”

If you go

What: "Art and the New England Farm"

Where: Florence Griswold Museum, 96 Lyme St., Old Lyme

When: Thought Sept. 16; 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tues.-Sat. and 1-5 p.m. Sun.; closed Memorial Day, July 4 and Labor Day

Admission: $10 adults, $9 seniors, $8 students, free for ages 12 and under

Contact: (860) 434-5542

Related events: The museum is offering a variety of events in conjunction with this exhibition. They include "Painting 'En Plein Air' in the Pop-Up Barnyard," which features a heifer and a miniature donkey, among other creatures, 1-4:30 p.m. June 2; "Picturing the New England Farm" with curator Amy Kurtz Lansing at 11 a.m. June 20; and "A Year at Tiffany Farm: A Conversation" with photographer Judy Friday at 11 a.m. Aug. 15. For more, visit florencegriswoldmuseum.org.

For the full article and more images Click Here