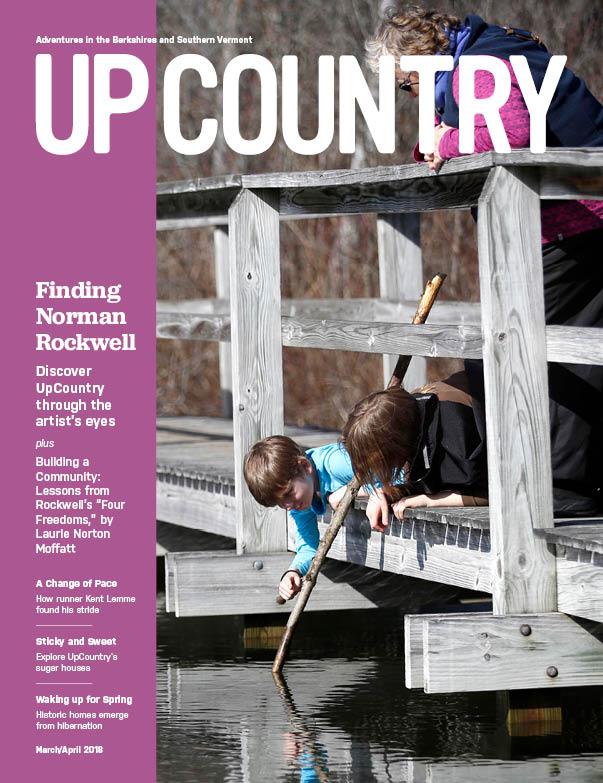

Behind the Scenes: Sleeping Houses

Across the Berkshires, historic homes are emerging from hibernation

By: Ruth Bass

Upcountry Magazine, March/April 2018

Photo: © The Berkshire Eagle

It’s March. The month of blizzards – or mud. And the month of awakenings. About now, the hundreds of black bears are rubbing their eyes, stretching and thinking about hunting down a bird feeder or two. Daffodil buds are stirring, tree buds are plumping up. And many of the Berkshires’ historic cottages are being shaken awake by their keepers.

It takes awhile for the former residences of the Frenches, the Choates, Suzy Frelinghuysen and George L.K. Morris, the Ashleys and John Sergeant to get going in the spring. That’s because so many things were done to these venerable tourist attractions last fall to ensure their survival in hibernation. Drained, blanketed, insulated and shrouded, they have been asleep for months.

Still, as any parents or guardians would do, the caretakers of these treasures peep in often to be sure all is well. They check to see that everything is where they left it, they make sure water isn’t dripping, that no wild animal, nor uninvited human, has gotten in (Naumkeag had a raccoon once).

Some rooms at Naumkeag, the summer home of Joseph Hodges Choate and his family in Stockbridge, Mass., look normal except for a few draped sheets. Others, like the dining room, stand stark in winter. But soon, in hopes of an April opening this year, the rugs will be unrolled, tablecloths put in place, dishware dusted and returned to tables. The operation, says Mark Wilson, curator of collections for the west region of The Trustees of Reservations, pretty much duplicates what the Choates did every year, as they rotated between their house in Stockbridge and their Manhattan mansion. The Choates had servants for the tasks now performed by the regular crew and volunteers.

The family use of Chesterwood was much the same. Daniel Chester French razed the farmhouse on the place the family bought in 1896 and built a summer house, not insulated for winter, despite the fact that the sculptor is on record as reluctant to return to New York each October. And as, perhaps, pioneers among locavores, both the Choates and Frenches had vegetables from their country estates, both which had functioning farms on them, sent to them in the city for as long as autumn frosts held off.

At Chesterwood, also in Stockbridge, where Daniel Chester French created the seated Lincoln statue for the Lincoln Memorial, veteran caretaker Gerry Blache drained and blew out all the pipes in the house, barn gallery and studio in late October. Of the ten structures on the 122-acre property, only the red cottage – the offices – stays open. The buildings are without heat except for the studio, which is kept at 32 degrees, maintaining a steady temperature to avoid moisture. Blache also doesn’t “want movement in that building anymore.”

In the fall, he and his crew move sculptures, box in the bas relief pieces on the studio porch, shut down the fountains, spread a couple inches of straw on the gardens designed by French and worry about the century- old pines that tower over the standing Lincoln statue and the nearby nature trails, which were also designed by the sculptor. “We pride ourselves that the center core is kept in a century-old manner,” he said.

Thus, in spring, he and his crew go into sharp reverse to plant the annals the Frenches would have, take care of the hydrangea trees that line the walk, and put the sculptures back. Even Executive Director Donna Hassler will put aside working on a new gallery space, which will include showing not only plaster studies of sculptures but French’s paintings. She’ll be climbing ladders to dust plaster casts and do whatever else spurs the race to spring.

Moisture is the demon in all these houses. At Naumkeag, they stopped covering some furniture pieces after they found mold on the undersides of tables. The stucco construction at Chesterwood makes moisture a constant concern, and regular inspections include making sure the walls aren’t actually wet. Dampness is the enemy of antique wallpaper at Naumkeag as well as wood veneers on the elegant furniture. Brian Cruey, general manager of Naumkeag for the Trustees of Reservations,says heating can actually damage the collections, especially major fluctuations in temperature. Right now, the cold inside the shuttered house is bone-chilling, but apparently the china thrives on it.

Upstairs, Wilson points out blue-checked sheets that shroud mattresses, chaises and beds. They may not be valuable, but they’re enduring – they’re the same ones the Choates used. One year, Wilson says, the family decided to try a Berkshire winter. It was 1887, and they stayed through Christmas. In January, they gave it up and fled to Florida. Care must also be taken with Naumkeag’s gardens, created after the death of the senior Choates. The water through the birch-lined stairway to Mable Choate’s gardens will soon run again, and the Diana statue in the linden alley will be uncovered. Other sculptures will come out of storage.

At the Frelinghuysen Morris House and Studio in Lenox, Mass., cold air, large expanses of glass and moisture combine as threats to art. Director Kinney Frelinghuysen keeps an eye out for leaks in the vulnerable flat roof of the International Style house where his aunt Suzy Frelinghuysen and uncle George L.K. Morris lived.

The first attempt at climate control for Morris’s enormous outdoor mural actually trapped moisture, so an old framework that Morris used has been installed in a new way, actually creating a little closet for the mural. That provides air, plus room for space heaters. It’s not glamorous, especially with the ragged edge of an insulating blanket visible on the flat room above. But so far, it’s doing the job.

Like the house and studio at Chesterwood, the Frelinghuysen Morris house is stucco, so interior walls easily start to sweat if conditions are right – or, more accurately, wrong. But here preservation is even more vital because Morris painted abstract works right on the walls of the living room. Frelinghuysen did the same in the dining room. Again, low tech solutions have been put in place, creating insulation on the windows. Unlike Naumkeag and Chesterwood, this museum is heated in the 60-degree range all winter. “We don’t mothball the house,” Kinney Frelinghuysen said, although it is open only to staff. Even with daily visits and heat, he admits, “If we get really nervous, we leave some faucets running.”

Morris built the studio on his parent’s Lenox estate, Brookhurst, in 1931. Nine years later, Berkshire architect John Butler Swann designed the connecting house where summer visitors enjoy the Frelinghuysen and Morris works, plus their collection of masterpieces. Some of the art is boxed for the winter some not, since this building is more snoozing than snoring. But it’s all vulnerable to the vagaries of Berkshire weather and must be protected in fall, unveiled in spring.

Things are simpler at Mission House and Ashley House, also Trustees of Reservations properties, since neither has infrastructure. They date back to the 1740s, so running water and other amenities don’t exist. Originally situated across the street from Naumkeag, Mission House, once the home of missionary John Sergeant, stands now at the corner of Sergeant and Main streets in downtown Stockbridge.

Ashley House gets the award as best sleeper in this small survey, not opening for tours until July and August, although the grounds are basically accessible all year. Situated in Ashley Falls, a village of Sheffield, Mass., it’s famous for being at the core of the town of Sheffield’s early cries for independence and, ironically, for being the Berkshire home for the famous slave MumBett, also known as Elizabeth Freeman, who supposedly overheard some of the independence talk as she did her chores. She set out to gain her freedom and successfully sued for it.

But whether ready early in April, Memorial Day weekend or a bit later, these houses – and several others in the county – wake slowly. It takes time to close the doors at the end of the season, and just as much time to throw them open again. Blache puts it succinctly, “April is crazy.” •

For full issue, article and images Click Here